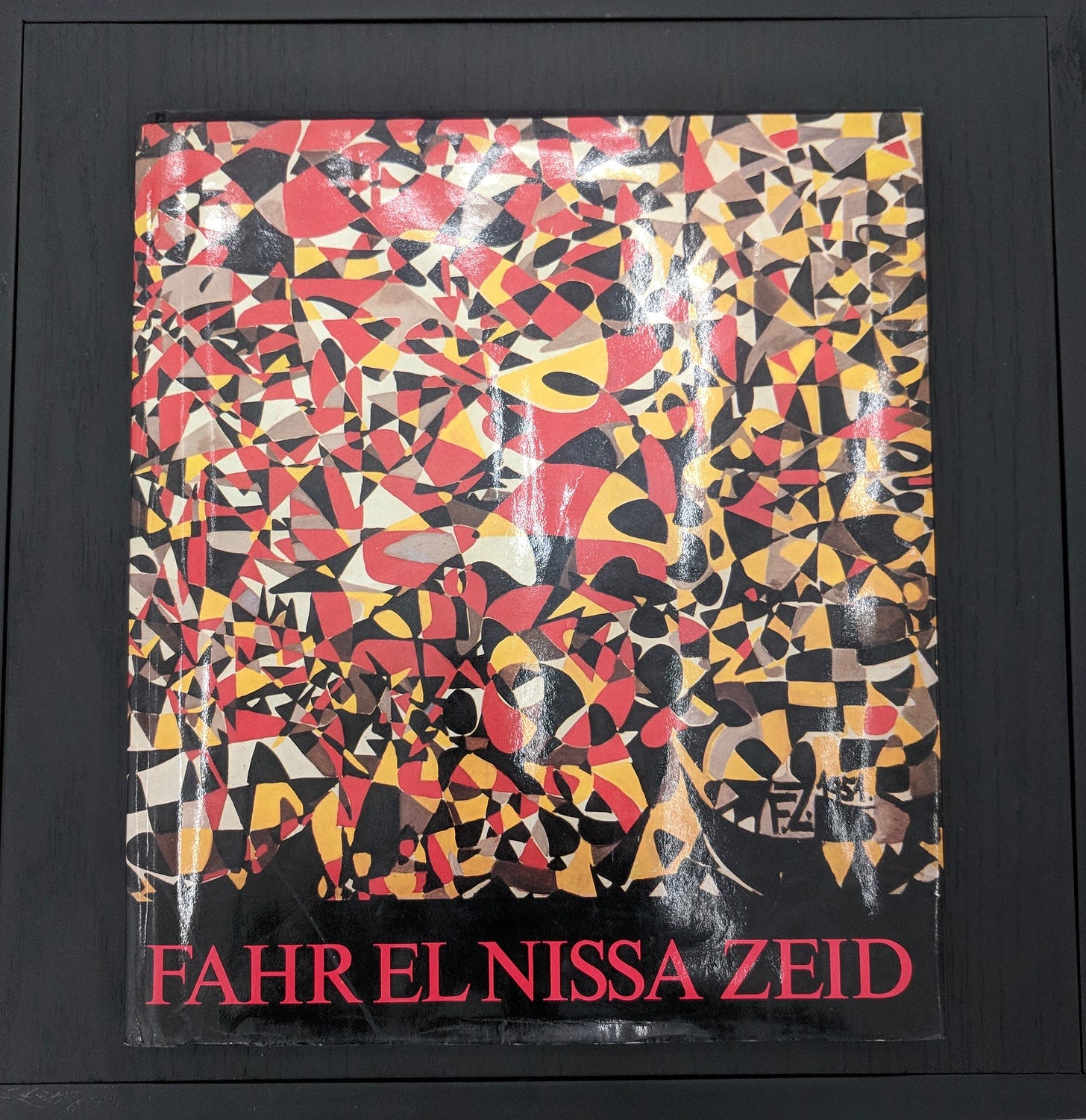

Two years back, on a day so unlike today, I was at the Dar Al Anda art gallery in Amman. While browsing through the pieces my eyes fell on a coffee table book in the middle of the room. A ballet of bold coloured abstractions filled its cover, and at the bottom just the name - Fahr El Nissa Zeid.

A few months back, as I was browsing through the photos from my trip, I chanced upon this photo. I had completely forgotten about it. I was struck again by the bold painting that adorned the book cover, just as I had that late July evening. I wanted to see more of the artist.

“I don’t think there’s any difference between an abstract and a portrait, because one could make a hundred portraits and every time it will be different. Because it is not a photo. It is the soul,” she says, in a video document that Tate made for her first retrospective. It happened in 2017, twenty six years after her death in 1991.

A reporter and a curator reviewed this exhibition together -

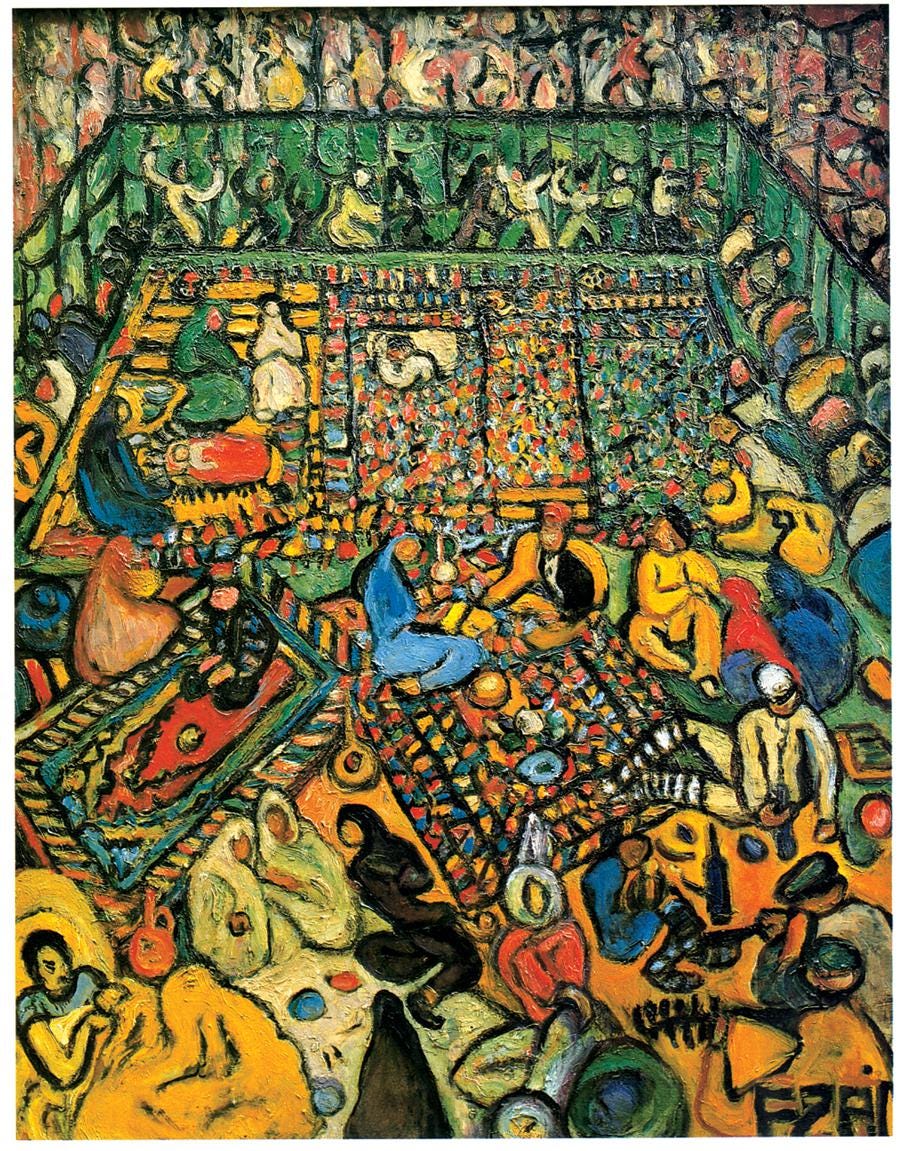

“When you consider what Rothko was doing, what Pollock was doing, and then what Fahrelnissa was doing on that scale, it’s pretty phenomenal. That she’d been forgotten is even more astonishing,” said Greenberg. Zeid’s large paintings stayed unequaled in scale by any women artist until Joan Mitchell’s triptychs in the 1960′s.

Zeid had fallen out of mainstream conversation till this retrospective. Everyone forgot. And then when they were reminded, everyone wrote of how she was forgotten. But to see her painting, even if it is a print, a hundredth of a size as I did, is to give into the arresting life in them. And you remember.

The retrospective was followed by a show in Turkey, where she was born. A review of that homecoming said -

Defying neat categorization, Zeid transcended boundaries. She combines some Eastern traditions in her embrace of European expressionism and abstraction. A progressive Muslim woman, she glided between avant-garde Turkish collectives, the Nouvelle Ecole de Paris, and, through marriage, into the Iraqi royal court. She moved through the heart of global modernism into relative obscurity by the end of her life.

That’s a good biography in a paragraph.

A little before the end of her life (more like a decade and a half before), she moved to Jordan. The purpose was to be with her son, a Hashemite prince of Jordan. But she ended up teaching women painting in Amman, and created an entire modern scene in Jordan’s art culture.

One of her students wrote her biography. I found a comprehensive and studious review of it, that reads -

Such a critical revisiting of Zeid’s work is a timely and much-needed contribution to the study of transnational feminist art histories. As Laïdi-Hanieh addresses some of the pivotal questions in art history, she successfully disrupts the art historical tropes on Zeid’s art extant in narratives. This lavishly illustrated book, featuring both Zeid’s art and a range of photographs showing her in different stages of her life (as a young woman from a high-profile Ottoman family, a fine arts student in Istanbul, a mother in Republican Turkey, a member of the royal Iraqi family, an emerging artist in Paris and a teaching artist later in her life in Amman) further elucidates the ways in which Zeid’s intertwined identities defined her distinct style and process of art-making.

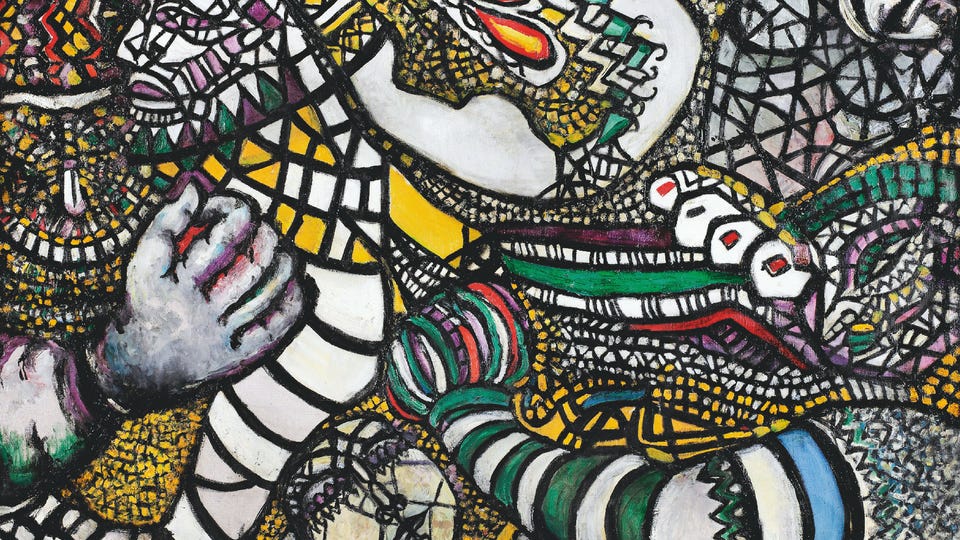

These are two self portraits, almost forty years apart.

As with all her portraitures, the eyes say the most. There is a curious element to the big bold eyes of her paintings. She once spoke of her switch to abstraction (which happened a little after the portrait on the left ‘43) about seeing farther than what the eyes see, to enlarge the visual orb. Perhaps all her eyes of all her portraits keep saying the same thing. She was 80 when she made the second portrait on the right. 10 years away from her death, almost turning and looking back at her life, seeing herself through and farther than the portrait she made almost forty years back, capturing the richness and colours and all her roots of her rootless life. Eyebrows raised still, curiosity never leaving the eye.

The Life of Fahr El Nissa Zeid

The scale and scope of her work alone should have made Zeid an example of artistic zenith. Her clarity of thought and purpose with her brush, puts her in the bracket of rare genius amongst artists. But the rootlessness, evident in her life and her art, took away from that legacy. The western world saw her as a hobby princess with skill, and her home saw her as an outsider pursuing western art philosophies. No one could see how well her colours of all her worldS mixed on the canvas. No one had the eyes. And no one saw her for what she was - a modern master.

Endnotes

Larah Arafeh writes a thorough but smaller biography of Fahr El Nissa that gives you all that you need to know about her storied life. Her life was as colourful and big as her canvas.

Matt Hanson gives a wonderful context to Zeid’s art and her life. You come to know of her clarity of thought and prolificacy of her work.

This is a beautiful account of the princess’ legacy to Arabic art and culture.

The picture on the book that I saw, is a part of her mammoth five meter wide masterpiece called My Hell.